・When a dog is diagnosed with lymphoma and left untreated, the prognosis is about 1-2 months.

・Even if a dog is diagnosed with malignant lymphoma, there may not be any noticeable changes in its condition initially, although lumps could appear on the surface of the body.

・Even if your dog has lymphoma, engaging in immune therapy can improve their condition or maintain their quality of life (QOL), helping them regain their vitality and appetite.

目次

- 1 About Canine Lymphoma

- 2 Overview of Canine Lymphoma

- 3 Types of Lymphoma in Dogs

- 3.1 Multicentric Type (Frequency: 80%) – Canine Lymphoma

- 3.2 Gastrointestinal Type (Frequency: 5–7%) – Canine Lymphoma

- 3.3 Thymic (Mediastinal) Type (Frequency: 5%) – Canine Lymphoma

- 3.4 Cutaneous Type (Rare Frequency) – Canine Lymphoma

- 3.5 Extranodal Type (Rare Frequency) – Canine Lymphoma

- 3.6 Abdominal Lymphoma – Canine Lymphoma

- 3.7 Classification by Type of Immune Cells – Canine Lymphoma

- 3.8 Classification by Malignancy – Canine Lymphoma

- 3.9 Classification by Severity – Canine Lymphoma

- 4 Symptoms of Canine Lymphoma

- 5 Examination of Lymphoma in Dogs

- 6 Treatment of Lymphoma in Dogs

- 6.1 Chemotherapy (Anticancer Drug Treatment) for Lymphoma in Dogs

- 6.2 Things to Check Before Starting Anticancer Drug Treatment

- 6.3 Surgery (Palliative Surgery) – Treatment for Canine Lymphoma

- 6.4 Other Treatments – Treatment for Canine Lymphoma

- 6.5 Treatment After Remission

- 6.6 Treatment Upon Lymphoma Relapse

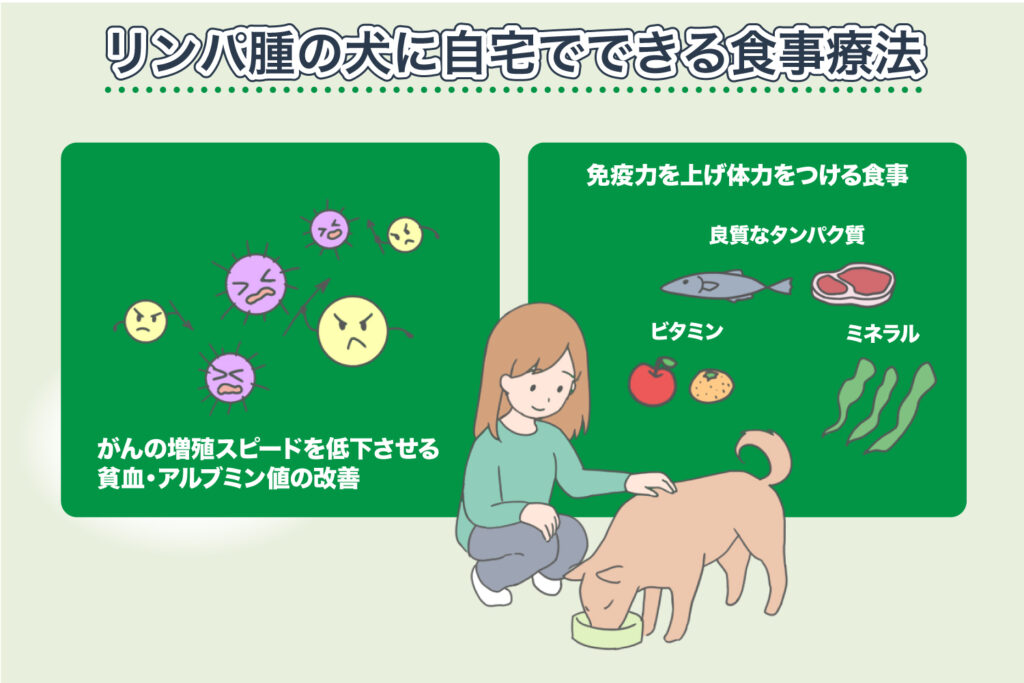

- 7 Homemade Dietary Therapy for Dogs with Lymphoma

- 8 Importance of Balancing the Immune System

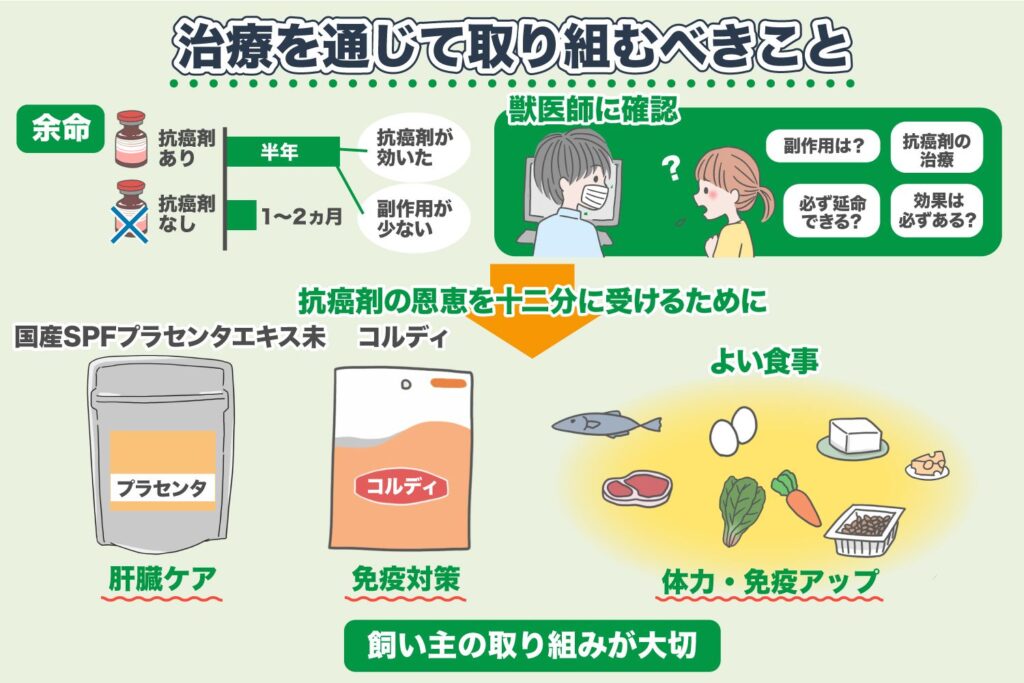

- 9 Things We’d Like You to Address Through Treatment

- 10 Cordy is recommended for managing side effects of anticancer drugs.

About Canine Lymphoma

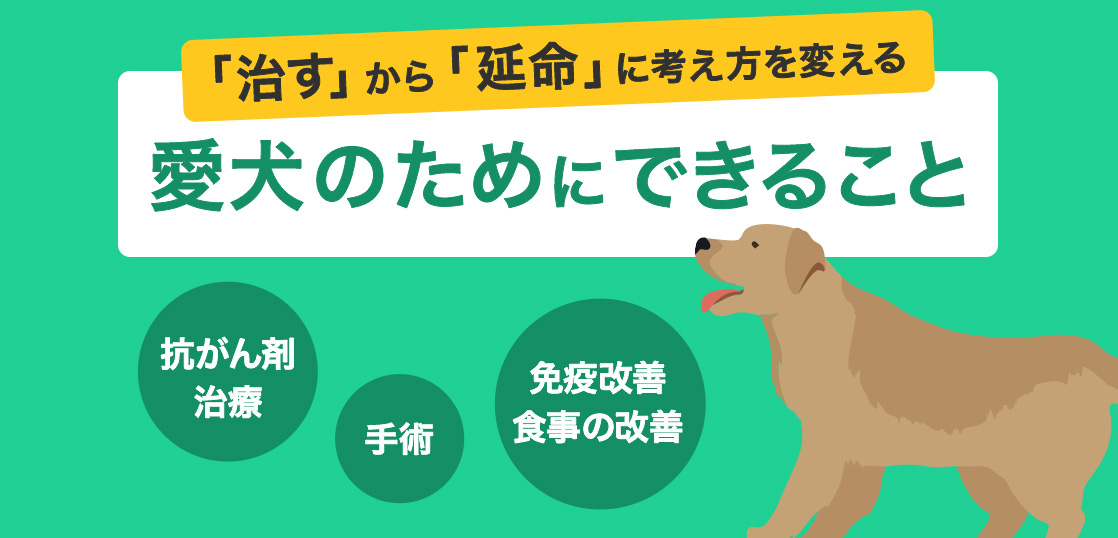

Lymphoma in dogs is a type of malignant tumor that can manifest as lumps or progress without forming lumps.

Among various cancers that occur in dogs, lymphoma is relatively common. It often develops in areas where lymphocytes tend to accumulate, such as lymph nodes, the thymus, and the digestive system. However, since lymphocytes circulate throughout the body, the disease can infiltrate various organs.

Generally, the prognosis for untreated cases is 1-2 months, while treatment can sometimes extend life expectancy to 1-2 years, as commonly explained by veterinarians.

While lymphoma is certainly a difficult disease to treat, there are cases where giving Cordyceps has helped dogs maintain their vitality and appetite for an extended period.

- Use Case of Cordy for Mesenteric Lymphoma in Dogs (Miniature Dachshund)

- Use Case of Cordy for High-Grade Intra-Abdominal Lymphoma in Dogs (Shih Tzu)

- Use Case of Cordy for Lymphoma in Dogs (Yorkshire Terrier)

- Case of Malignant Intra-Abdominal Lymphoma in Cats (1-Month Prognosis, Lung Metastasis) Disappearing

- Case of Long-Term Maintenance of Condition in a Cat Suspected of Having Lymphoma

- Improvement Case of Spleen Cancer in Cats (Lymphoma/Mast Cell Tumor)

- Case of Controlling Lymphoma/Thymoma in Rabbits Without Burden

Canine lymphoma is a type of cancer that can occur throughout the body, primarily developing from the lymph nodes but can also originate from organs.

There are types of canine lymphoma that progress by forming lumps (masses), similar to other malignant tumors, and there are also types that do not form lumps as they progress.

Overview of Canine Lymphoma

Malignant lymphoma in dogs is a systemic cancer classified as a “cancer of the blood.”

The mortality rate for dogs suffering from lymphoma is extremely high, and in current veterinary medicine, it is considered an incurable disease.

Lymphoma cells in dogs (cancerous lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell) do not stay in one place.

They proliferate and spread throughout the dog’s body.

As lymphoma progresses, it drains the dog’s vitality, invades the lungs, and can sometimes form masses that cause intestinal obstruction, ultimately leading to the dog’s death.

Generally, the life expectancy is 1-2 months without treatment, but if treatment is effective, life can be extended to about 1-2 years.

Representative breeds prone to malignant lymphoma include:

- Golden Retriever

- Beagle

- Poodle

- Shepherd

The treatment for malignant lymphoma is almost fully established and largely standardized.

※ “Established treatment” does not equal “cure”

The main treatment is chemotherapy. In addition to chemotherapy, steroids may also be used. If the treatment goes well, there is a possibility of remission. However, remission is usually temporary, and most dogs relapse. Post-relapse treatments are considerably challenging.

When treating canine lymphoma, the primary goals are to achieve remission at all costs and to prevent relapse, thereby prolonging remission.

In other words, the general treatment approach for canine malignant lymphoma focuses on “prolonging life” rather than aiming for a “cure” from the outset.

However, remission is different from “cure.”

The cancer cells (lymphoma cells) have not disappeared but are lurking in various parts of the body.

As a result, a recurrence is inevitable. Often, recurrence occurs within a few weeks to a year.

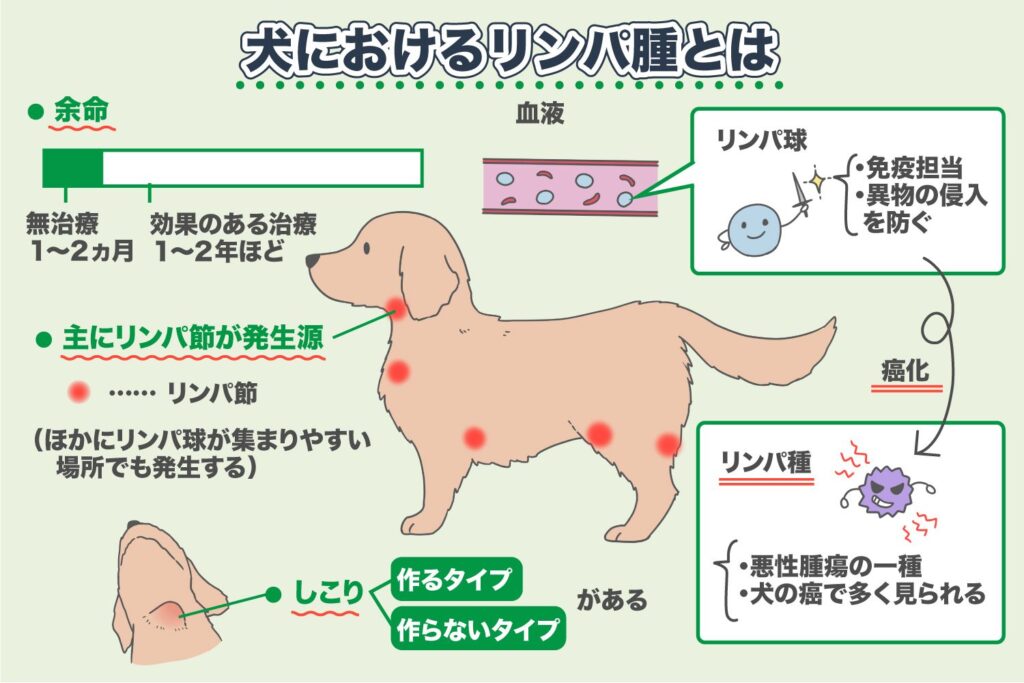

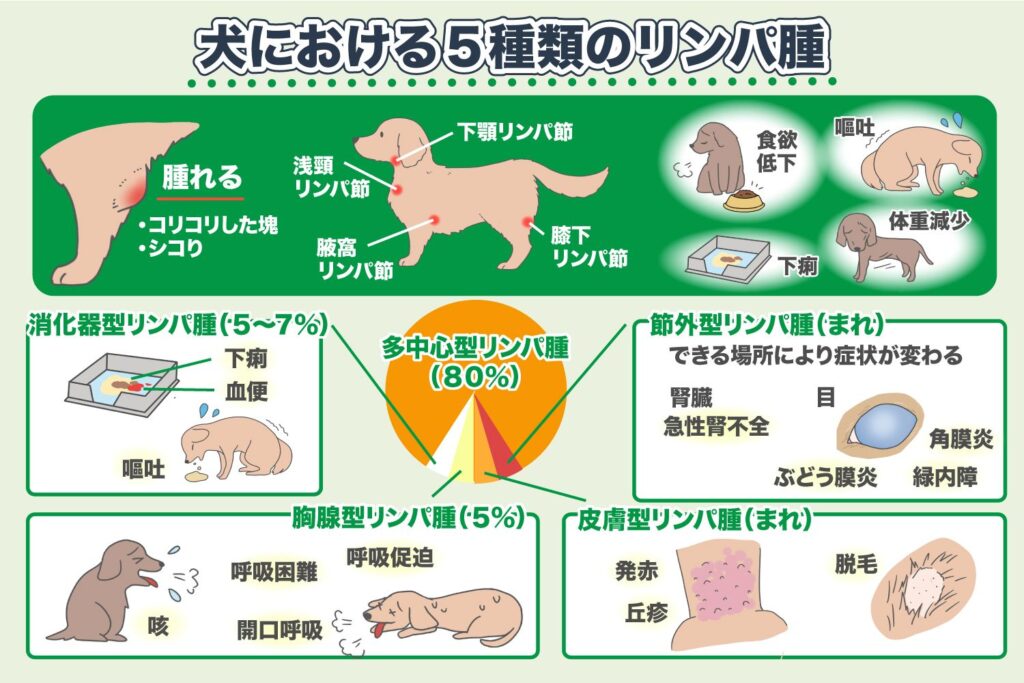

Types of Lymphoma in Dogs

Lymphoma in dogs can be classified into five types.

- Gastrointestinal lymphoma, which develops in the digestive system

- Multicentric lymphoma, characterized by the swelling of peripheral lymph nodes

- Cutanous lymphoma, occurring in the skin and oral mucosa

- Thymic (mediastinal) lymphoma, developing near the heart, thymus, or in the area between the lungs known as the mediastinum

- Extranodal lymphoma, occurring in organs such as the central nervous system and kidneys

Below, we explain the characteristics of each type of lymphoma.

Multicentric Type (Frequency: 80%) – Canine Lymphoma

Typically, the swollen lymph nodes include those under the jaw (submandibular lymph nodes), neck (superficial cervical lymph nodes), under the armpits (axillary lymph nodes), and behind the knees (popliteal lymph nodes).

If you notice a hard lump or nodule on your dog’s body surface, it could be indicative of lymphoma. We recommend that you seek a veterinarian’s examination as soon as possible.

Symptoms may include a decrease in appetite, vomiting, diarrhea, and weight loss in addition to the swelling of the lymph nodes. As the condition progresses, it can infiltrate the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.

Often, no symptoms other than lymph node enlargement are observed, making it important to regularly feel your dog’s body and promptly notice any swelling in the lymph nodes.

※It is important to note that swelling of the lymph nodes does not necessarily indicate lymphoma; it can also be due to bacterial or viral infections causing inflammation.

Gastrointestinal Type (Frequency: 5–7%) – Canine Lymphoma

As the disease spreads in the digestive system and absorption decreases, symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting, and bloody stools, which resemble common gastrointestinal issues, may appear. These symptoms can often be confused with typical digestive problems, making it challenging to diagnose.

If your dog exhibits diarrhea, vomiting, or loss of appetite for several days, or if you notice sudden weight loss, there may be a possibility of gastrointestinal lymphoma. We recommend visiting an animal hospital.

If gastrointestinal symptoms persist or cannot be controlled with medication, it is advisable to undergo imaging diagnostics such as X-rays, ultrasound, and endoscopy, as well as blood tests to examine the ‘serum protein electrophoresis.’

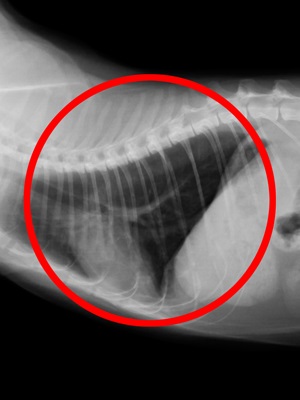

Thymic (Mediastinal) Type (Frequency: 5%) – Canine Lymphoma

Since it occurs within the thoracic cavity, symptoms like coughing, difficulty breathing, rapid breathing, and open-mouth breathing can be observed. As it progresses, gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea may also appear.

Additionally, unlike other lymphomas, it is characterized by a high tendency to develop hypercalcemia.

If your pet shows persistent symptoms of rapid breathing or coughing, it could be a sign of thymic lymphoma, so please visit a veterinary clinic as soon as possible.

Cutaneous Type (Rare Frequency) – Canine Lymphoma

It shows symptoms similar to general dermatitis, such as redness, hair loss, and papules, although it occurs rarely. Cutaneous lymphoma can also occur on the oral mucosa.

Due to the symptoms being similar to those of dermatitis, it can be challenging to diagnose lymphoma solely based on skin symptoms. It is often misdiagnosed as dermatitis, with conditions like seborrhea, atopic dermatitis, or pyoderma frequently being confused with it. When skin treatments, including antibiotics, fail to produce a response, lymphoma may be suspected for the first time.

Although rare, if it turns out to be lymphoma, early treatment is desirable, so it is recommended to have an examination promptly.

Extranodal Type (Rare Frequency) – Canine Lymphoma

- multicentric type

- gastrointestinal type

- cutaneous type

Extranodal lymphoma typically develops in organs such as the eyes, central nervous system, and kidneys.

The symptoms vary depending on the affected area. For example, lymphoma in the kidneys may present symptoms of acute renal failure, while lymphoma in the eyes may cause ophthalmic symptoms like uveitis, keratitis, and glaucoma.

Abdominal Lymphoma – Canine Lymphoma

Although it is classified differently from the above categories, you might hear your vet refer to abdominal lymphoma or lymphoma located in the abdominal cavity. This term is used when lymphoma is found in internal organs such as the liver, spleen, mesentery, or intestines within the dog’s abdominal cavity.

Abdominal lymphoma may include lymph node tumors in the mesentery, gastrointestinal lymphoma, liver lymphoma, and others.

Since this is a lymphoma that develops in internal organs, as the tumor enlarges, it can compress the organs within the abdominal cavity, causing respiratory issues (such as labored breathing and difficulty breathing), digestive symptoms such as decreased appetite, vomiting, and weight loss.

Classification by Type of Immune Cells – Canine Lymphoma

Lymphocytes are divided into two types: T cells and B cells, so canine lymphoma can also be classified as T-cell lymphoma and B-cell lymphoma based on the type of lymphocytes that have become cancerous.

T-cell lymphoma progresses slowly but is less responsive to chemotherapy. In contrast, B-cell lymphoma progresses quickly but is generally more responsive to chemotherapy.

Classification by Malignancy – Canine Lymphoma

Lymphoma in dogs can be categorized into high-grade (high malignancy, low differentiation) and low-grade (low malignancy, high differentiation) based on the level of malignancy.

High-grade (high malignancy, low differentiation) lymphoma progresses extremely fast, but it is not uncommon for chemotherapy to temporarily reduce the tumor.

In cases of high-grade lymphoma, a multi-drug regimen may be used, combining several potent chemotherapeutic agents.

Since the response to chemotherapy is good, there can be temporary remission (where the dog appears healthy both visually and in tests), but eventually, drug resistance may develop, making the chemotherapy ineffective.

The prognosis is expected to be poor if the tumor enlarges after remission.

On the other hand, low-grade (low malignancy, high differentiation) lymphoma progresses slowly, and dogs with this type of lymphoma may live for a long time even without special treatment.

Furthermore, if chemotherapy is applied, it may be possible to use a single chemotherapeutic agent over a long period while monitoring the condition.

Classification by Severity – Canine Lymphoma

It is said that the higher the stage, the worse the prognosis, meaning a shorter lifespan.

The stages are classified into five levels based on the degree of infiltration into the lymph nodes, with sub-stages a (no symptoms) and b (with symptoms) defined based on the presence of systemic symptoms.

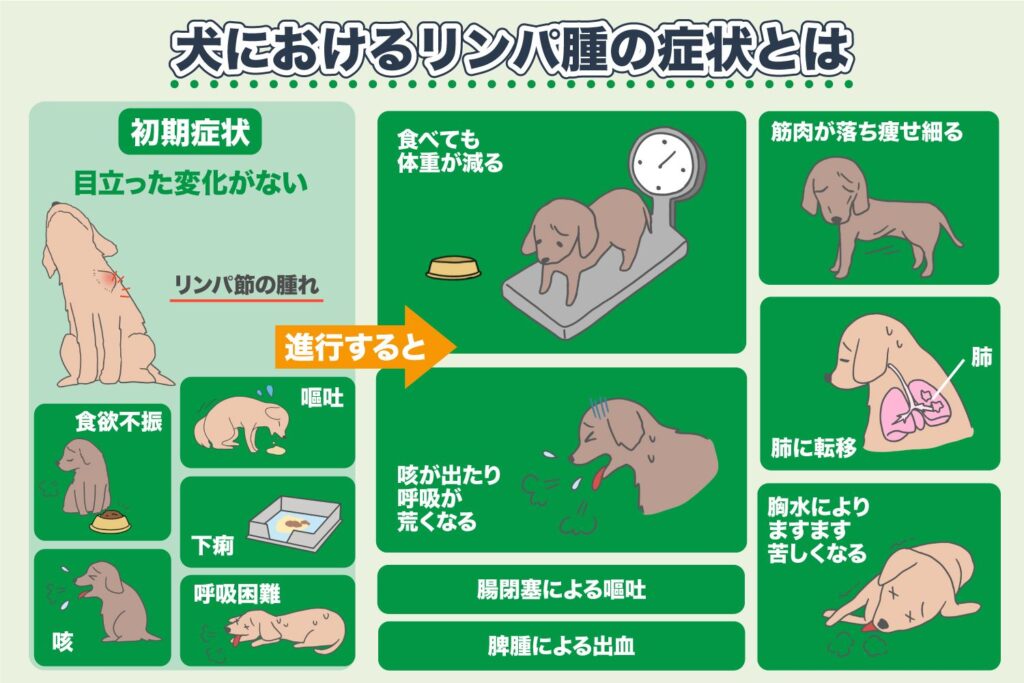

Symptoms of Canine Lymphoma

Early Symptoms of Lymphoma in Dogs

Swelling of the lymph nodes around the neck or the base of the legs is common. You might feel hard lumps when touched.

Some owners notice these hard lumps during regular petting sessions.

However, in reality, it is difficult for owners to detect malignant lymphoma in their dogs at the early stage.

Most cases are discovered during regular check-ups or examinations for other illnesses when veterinarians notice abnormalities and conduct precautionary tests. It can also be identified if a groomer points it out.

Additionally, in cases of lymphoma types such as gastrointestinal or mediastinal lymphoma that occur inside the dog’s body, you almost never feel the lumps in daily life.

In such cases, symptoms like reduced appetite, vomiting, diarrhea, or respiratory symptoms like coughing and difficulty breathing might be observed.

※ Swelling of the lymph nodes is not always caused by malignant lymphoma.

It can also be due to bacterial or viral infections.

In fact, it is more often caused by diseases other than malignant lymphoma, but it is recommended to visit a veterinarian early for confirmation.

Symptoms of Advanced Malignant Lymphoma in Dogs

As the number of cancerous cells increases, the dog gradually loses energy, its appetite decreases, and it starts losing weight.

- Despite eating, weight loss does not stop

- Gradually, muscle mass decreases, and the dog visibly becomes thin

- The malign lymphoma in dogs progresses and metastasizes to the lungs

- As lymphoma metastasizes to the lungs, the dog starts coughing and breathing becomes more labored

- Pleural effusion may accumulate, making breathing significantly more difficult

Lymphoma cells may form masses around the intestines, causing intestinal obstruction. The dog may vomit out food due to this obstruction.

The spleen may also swell, and in severe cases, it can rupture and cause massive bleeding.

If spleen rupture occurs, immediate medical attention is required.

Examination of Lymphoma in Dogs

General Examination Flow Until Treatment for Lymphoma in Dogs Begins

If the dog is vomiting, the condition of the gastrointestinal tract needs to be known; if breathing is labored, the condition of the lungs needs to be assessed.

The spleen, which tends to swell, will also be observed. Imaging tests will likely be performed for these organs.

For a final confirmed diagnosis, there are methods like fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy to extract cells from the swollen area or surgical extraction of tissues.

If the swollen area is large, FNA can usually yield sufficient cells. However, if the swollen area is small and not enough cells can be obtained, it might lead to an incorrect diagnosis.

The diagnosis is determined based on whether cancer cells are present in the excised tissue.

No matter how suspicious the previous tests seem, if no malignant cells are found, lymphoma cannot be definitively diagnosed.

Without a confirmed lymphoma diagnosis, chemotherapy cannot begin.

The detected lymphoma cells are examined to determine whether they are high-grade or low-grade.

Additionally, the cells are classified as B-cell or T-cell type.

Generally, high-grade lymphomas and T-cell lymphomas progress slowly but are less responsive to chemotherapy.

Conversely, low-grade lymphomas and B-cell lymphomas progress rapidly but respond better to chemotherapy.

Since low-grade lymphomas often respond well to chemotherapy, it is not uncommon for the cancer to temporarily shrink or for the dog’s condition to improve.

However, because low-grade lymphomas progress extremely quickly, even if the cancer temporarily shrinks to the point where it’s no longer visible in imaging or palpable by touch, it tends to grow back rapidly.

Once the lymphoma develops resistance to the chemotherapy, the drugs become ineffective, and the cancer spreads.

Genetic testing for canine lymphoma has also become more common recently.

This testing is used to establish a treatment plan, predicting which chemotherapy might be effective by discerning between B-cell and T-cell lymphomas.

High-resolution imaging tests, such as CT scans or MRIs, are not always necessary.

These imaging tests place a significant burden on the dog and are also expensive.

It is recommended to thoroughly consult with a veterinarian to confirm if there is any benefit to having a CT or MRI scan after a lymphoma diagnosis, and proceed with the test only if necessary.

Examinations During Treatment of Canine Lymphoma

When a dog undergoes chemotherapy for lymphoma, it is likely recommended to conduct tests during treatment to check if the chemotherapy is effective and to monitor the severity of side effects.

While excessive testing is not advisable due to the strain it places on the body, tests that determine whether the chemotherapy is working can be very beneficial. They can help in discontinuing ineffective or excessively strenuous treatments.

Treatment of Lymphoma in Dogs

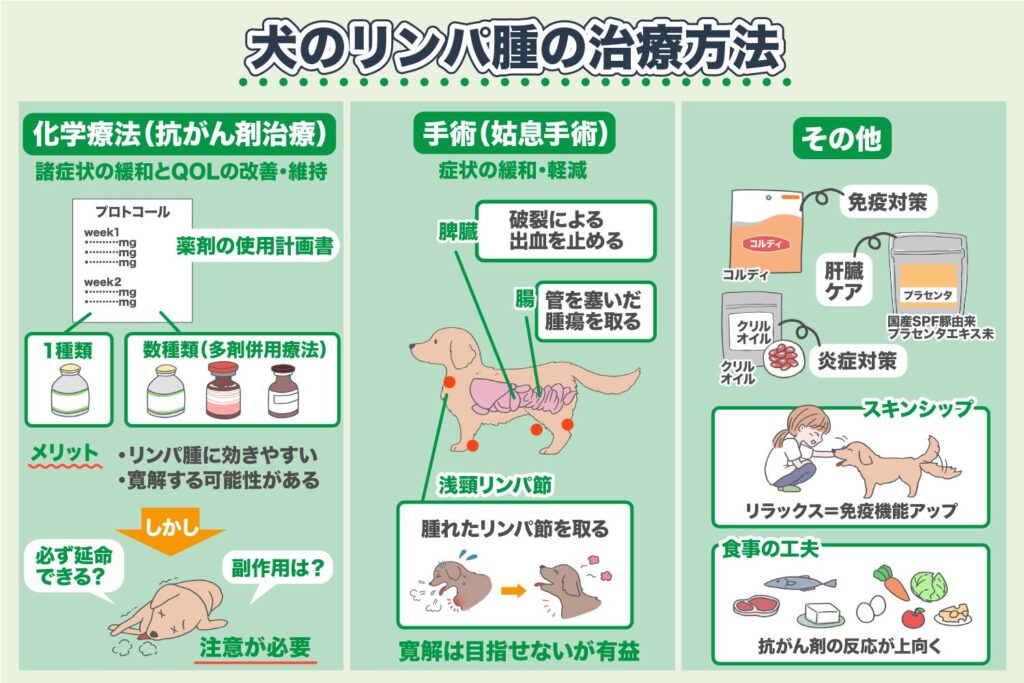

Chemotherapy (Anticancer Drug Treatment) for Lymphoma in Dogs

The general treatment for malignant lymphoma in dogs is chemotherapy, that is, anticancer drug treatment.

Lymphoma in dogs is a systemic blood cancer, and it is a type of cancer that responds well to anticancer drugs.

Therefore, the only possibility for remission is through chemotherapy.

Steroids are not anticancer drugs but are often used.

There are many types of anticancer drugs used in the treatment of lymphoma in dogs. Sometimes only one type is used, and other times multiple anticancer drugs are combined.

Using multiple anticancer drugs has the benefits of being more effective and spreading out side effects compared to administering a single drug in large doses. However, it requires more attention to the side effects.

In the treatment of lymphoma, it is common to use a protocol that combines several anticancer drugs, as opposed to using only one.

Combination therapy involves using two or three different anticancer drugs with varying characteristics and side effects, which can prevent bias in side effects and increase the effectiveness.

For lymphoma, treatment follows a manual known as a “protocol” which specifies which drugs to use and when to use them.

However, there are types of lymphoma that do not respond well to anticancer drugs, and in such cases, anticancer drugs may not be actively used.

The significance of using anticancer drugs is to “alleviate various symptoms caused by the tumor and improve and maintain QOL (quality of life),” but focusing solely on completing the protocol may lead to loss of life due to severe side effects.

During chemotherapy, it is important to monitor and ensure that your dog’s QOL is maintained.

About Anticancer Drug Protocols and Types

Lymphoma is a type of tumor that often responds well to anticancer drugs, but if the focus is solely on completing the protocol, it is not uncommon for pets to lose their lives because severe side effects were overlooked or the treatment was continued despite severe side effects.

Some veterinarians may say, “Pets do not experience severe side effects like humans,” but since dogs and cats cannot speak, it is possible to miss signs of their minor ailments even if they try to show them.

Moreover, animals have a natural instinct of “not showing weak points (= in the wild they would be preyed upon)” and may hide symptoms they can endure.

Side effects of anticancer drugs often become evident 3-4 days after administration, so please monitor any changes in appetite, activity levels (such as how long they stay awake or their stamina during walks).

Things to Check Before Starting Anticancer Drug Treatment

When told “the prognosis is 1-2 months without treatment,” we are prone to think that we have no choice but to entrust everything to the veterinarian.

If the treatment is successful, your dog’s condition improves, and lymphoma is cured, it may be okay to leave everything to the veterinarian.

However, in reality, although chemotherapy can achieve temporary remission, it is uncommon for the condition to stabilize or for lymphoma to be cured over the long term.

Nevertheless, if owners (family members) take proper measures at home, they can help control and slow the progression of lymphoma.

As a result, your dog’s quality of life (QOL) may improve, and he/she might maintain good spirits and appetite while living with or even overcoming lymphoma.

When told, “If your dog undergoes anticancer drug treatment, he/she might live for another six months; otherwise, only 1-2 months,” that is only if the anticancer drugs are highly effective with minimal side effects.

It is recommended to ask your veterinarian whether the treatment will definitely extend your dog’s life, if there will be no loss of energy due to side effects, and if the treatment will certainly be effective.

If you decide to go forward with anticancer drug treatment, we suggest considering Cordy for immune support and domestically produced SPF pork-derived placenta kiss powder for liver and kidney care to manage side effects.

- About Anticancer Drugs Used in Cancer Treatment for Dogs and Cats — Side Effects, Precautions, etc.

- About Targeted Cancer Therapies Used in Cancer Treatment for Dogs and Cats

- Types and Protocols of Chemotherapy and Anticancer Drugs Used for Lymphoma in Dogs and Cats

- Minor Exposure to Anticancer Drugs — Caution with Anticancer Drugs During Pet Cancer Treatment

“`html